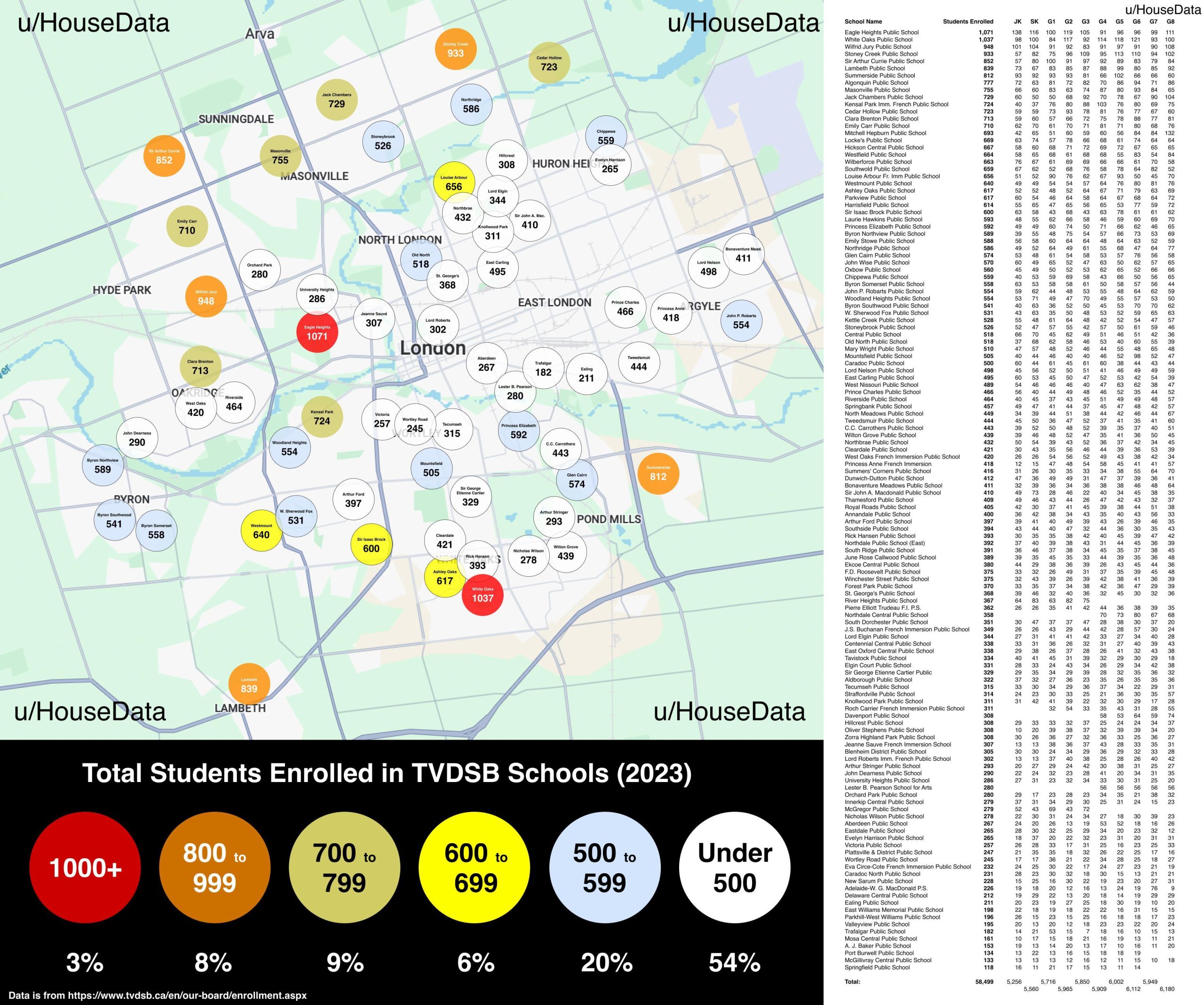

London parents are keeping a close eye on Thames Valley District School Board’s next moves after recent speculation about potential school closures sparked heated online discussions. The conversation gained momentum when enrollment data revealed dramatic differences between schools across the city, with some struggling to fill classrooms while others burst at the seams.

The numbers paint a telling picture of London’s educational landscape. While schools like White Oaks Public School and Stoney Creek Public School are managing nearly 1,000 students each, smaller community schools in central areas are operating with enrollment figures in the low hundreds. This disparity has become a focal point for parents wondering which schools might be on the chopping block.

Local families are particularly concerned about the funding model that drives these decisions. School boards receive per-student funding, meaning schools with lower enrollment get less money to operate – even though maintaining a building costs roughly the same whether it’s full or empty. When enrollment drops below 60% capacity, which projections suggested would happen to most schools, the financial strain becomes unsustainable.

The geographic patterns emerging from the enrollment data tell their own story. Schools in newer developments on the city’s edges tend to have higher numbers, while older community schools in established neighbourhoods often struggle with lower enrollment. This trend reflects London’s growth patterns, where families with school-age children gravitate toward newer housing developments.

Parents have been vocal about their frustrations with the current system, particularly the strict boundary rules that determine which school children must attend based on their home address. Many argue this creates artificial overcrowding in some areas while leaving perfectly good schools underutilized elsewhere.

The situation becomes more complex when considering school capacity. Some schools reporting lower absolute numbers might actually be at or over capacity due to their smaller physical size, while larger schools with higher enrollment numbers could still have room for more students. The data shows raw enrollment figures without accounting for each school’s actual capacity limits.

Transportation costs add another layer to the funding puzzle. Operating multiple smaller schools requires more buses and drivers compared to consolidating students into fewer, larger facilities. However, proposals to close underutilized schools and build newer, larger consolidated schools have faced significant pushback from parents who prefer smaller learning environments.

The recent influx of new residents to London through immigration and interprovincial migration might provide some relief to enrollment pressures, though it’s unclear whether this population boost will be enough to keep struggling schools viable. Immigration patterns tend to concentrate in certain areas of the city, potentially helping some schools while leaving others unchanged.

High schools are already undergoing boundary changes, with parents in affected areas expressing concerns about their children being moved to different schools. The elementary system could face similar restructuring if enrollment trends continue, though moving younger students tends to generate even stronger parental opposition than high school changes.

Adding to the complexity is the upcoming wave of children born during the pandemic who will be entering the school system. These “COVID babies” could significantly impact enrollment numbers over the next few years, potentially alleviating some capacity concerns at schools currently struggling with low numbers.

The Westminster Park area exemplifies the challenge facing school boards. Three schools – Arthur Stringer, Wilton Grove, and Nicholas Wilson – all operate in close proximity with relatively low enrollment numbers. While closing one or two might seem logical from a financial perspective, the remaining schools lack the physical space to accommodate all students without extensive use of portable classrooms.

Meanwhile, schools like University Heights continue adding portables to handle overflow, despite being physically tiny facilities. The school can’t accommodate many more students without complete reconstruction, highlighting how building limitations complicate simple solutions to enrollment imbalances.

Thames Valley District School Board has since clarified that no schools are currently being closed, but the underlying funding and enrollment challenges remain. The board continues to monitor enrollment patterns and assess long-term sustainability for all facilities across the district.

The enrollment data, compiled from the board’s official 2022-2023 figures, covers approximately 65 elementary schools within London city limits out of 131 total TVDSB schools. These numbers don’t include Catholic schools or other educational institutions outside the Thames Valley system, which serve additional students across the city.

Local online communities, including discussions on Reddit, continue to track these developments as parents seek clarity about their children’s educational future.